Representation of the Spirit: The Quest of Eternality in the Art of Cen Long

Author | Dr. Chen Kuang-Yi

10/6/2023

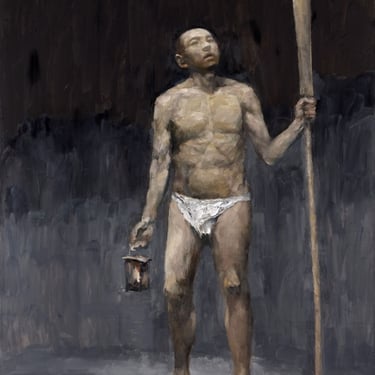

In the vibrant and tumultuous world of contemporary art, Cen Long's paintings stand out due to their distinctive restraint and simplicity. This simplicity derives primarily from uncomplicated compositions and a sober color palette. While Cen had previously explored various landscapes--scenes from Henan, Hubei, Tibet, Xinjiang, and other regions--as well as experimented with complex compositions, the creation of the monumental triptych Purgatory (inspired by Dante's description of the purgatory in Divine Comedy in 2010) marked the beginning of an entirely new phase in his artistic journey. At the center of this work is an intricately gnarled ancient tree bathed in moonlight. On the left panel, there is a monk bending down to light an oil lamp on a rocky path, while on the right panel, a sailor raises a lantern amidst the sails in the dark night. The half-naked male figures exhibit well-defined muscles, and their disproportionately large limbs convey a sense of solemnity in their posture as laborers. Simultaneously, they bring light and hope to the arduous and solitary journey through the rugged darkness of the night.

Since then, Cen has been deeply immersed in this style of creation. He predominantly employs black, white, and gray tones, complemented by warm ochres, earthy browns, and cold indigo to enhance his compositions. He keeps the color saturation subdued to maintain a neutral color palette. Making use of his proficiency in sketching and manipulation of form, he exaggerates the proportions of his figures, and utilizes light and shadow to add a sense of rounded solidity. His compositions centered on characters become increasingly minimalistic. Though he may depict small groups of individuals or include animals, he often focuses on a single figure while leaving the background rudimentary — filled in with bold single-color strokes or with only rough bands of color to indicate the horizon. This approach unmoors the works’ sense of time and space, conveying a timeless quality. As for the figures depicted in his paintings, they often wear simple attire, and in some cases, are partially or entirely nude from the waist up, covered only by draped garments as seen on ancient Greek statues. The nudity carries profound symbolism; by eliminating the clothing that symbolizes a person's social status, Cen returns the figures to their most authentic and primal state. Furthermore, in classical tradition, nudity represents the idealized human form, a symbol of spiritual freedom associated with heroes and deities.

These figures in Cen’s works still appear to be the farmers, shepherds, fishermen, woodcutters he has long focused on—their actions, the assisting animals, and the surrounding objects indicating their roles—collectively portraying a simple life in harmony with nature and the values of labor. In his new series, however, Cen has departed from specific depictions of individuals, events, times, places, and objects. The figures in his paintings have lost their specific meanings and contexts. Albeit, upon closer examination, subtle connections are suggested between the paintings. For example, the man in Starry Sky (2021) who holds an oar in his left hand and a lantern in his right while gazing at the stars, or the two individuals in A Windy Day (2019) strenuously raising a sail, might they be related to the sailor in Cen’s Purgatory? The presence of recurring motifs such as the cross-shaped staff, the praying youth with closed eyes accompanied by a white dove in A Gospel (2018), or the Christ-like woman searching for and rescuing a lost lamb in The Lost Lamb (2016), might indeed serve as counterparts to the monk in Purgatory. It's reasonable to suspect that these recurring motifs—such as boats, sails, oars, lanterns, stars, sheep, white doves, ancient trees, and others—are meaningful metaphors. Alternatively, they could function as flexible symbols without static signification, spontaneously evoking rich interpretations, open to various readings.

It's worth noting Cen’s use of the polyptych format. While not necessarily exhibited side by side, the similarities in sizes and shapes of many of his paintings, as well as the thematic resonance between them, form a conceptual polyptych. Polyptychs descend from altarpiece paintings and not only carry religious connotations but, as Deleuze pointed out, can also be likened to the division of rhythms in music or fundamental rhythmic forms in movement. He suggests that due to the multitude of movement animating the paintings, the rules of polyptych represent a "movement of movement" or a complex state of forces. The use of multiple panels in Cen's artwork undoubtedly introduces a sense of rhythm, movement, and power that goes beyond what can be achieved by individual paintings. The interplay of symbols and formal features that connect the panels constructs a complex symbolic system, replete with opacity and potential, inviting viewers to decipher the mysteries of the artist's inner world. This metaphorical style of painting places Cen within the realm of symbolism. The simplicity of composition, monumental dimensions, modest colors, and powerful, bold brushstrokes all contribute to the gravity in his works. It seems that the artist is endeavoring to create a place of spiritual solace amidst the chaos and noise of the contemporary world.

Cen’s immersion in Western classical paintings from a young age has left a profound mark on his work. The observation of his distinctive creative principles leads to the conclusion that he draws inspiration from Western classical aesthetic thought and iconic masterpieces. Since ancient times, philosophers like Plato and Aristotle have regarded the essence of painting as "imitation," la Mimèsis, with the emphasis that the object of imitation must be the noblest aspects of human actions to fulfill the educative function of art. Indeed, Cen's emphasis on suppressing color and prioritizing the "disegno" (Italian for "drawing") style of painting aligns with the approach advocated by Vasari in the 16th century. Vasari championed the idea that "disegno" encompasses not just "depiction" but also "conception," "intention," and "invention." It goes beyond the representation of the contours of objects; it is a "representation of the spirit" (représentation mentale). Masters of classicism similarly believed that the suppression of sense-captivating colors could better serve the purpose of representing the spiritual essence.

Cen's art, built upon such a profound aesthetic foundation, indeed are rich in philosophy and spiritual depth, capable of engaging in a dialogue with the masterpieces of art history. His The Lost Lamb resonates with the emotional depth of Rembrandt’s The Return of the Prodigal Son, while The Gal and Her Friend (2015) captures the dignity of laborers akin to Jean-François Millet's The Gleaners. Sowing Hope (2017), The Path to Home (2018), and Kinsfolk (2022) evoke the simple yet heartfelt familial emotions, reminiscent of the sincerity found in Millet's The Return from the Fields or The Evening Star. Cen's homage to classical art is undoubtedly sophisticated. He doesn't simply mimic the works of his predecessors but instead uses the timeless literary and artistic classics that have touched the hearts of generations as spiritual nourishment. He repeatedly contemplates and assimilates these classics, incorporating them as creative sustenance. This results in the ordinary figures in his paintings each possessing heroic spirits and noble souls.

Cen’s inheritance of Western aesthetics and classical masterpieces strikes a different chord from the modern trends; his works appear neither avant-garde nor fashionable, neither appealing to the trending topics nor the flexibilities of the contemporary art market. However, I think that the comparison of Cen’s work to that of the Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum is insightful and thought-provoking. The latter similarly despairs and loathes contemporary art and its trends, while being deeply touched by Rembrandt. They reject cultural bureaucratization, focusing instead on their inner worlds and the timeless themes found in classical art. Both similarly found refuge in Dante’s purgatory as a symbolic context for their artistic creations. Purgatory is a place where souls await redemption, and in a sense, painting becomes a form of salvation for both artists, a means of transcending the limitations of the contemporary art world and expressing their reverence for the divine and the sublime. While their works may not align with the current trends in contemporary art, artists like Cen and Nerdrum remind us of the enduring power of classical aesthetics and timeless themes. We perhaps could coin this approach to art as anti-modern. It's interesting to note that Baudelaire acknowledged the dual aspects of art in his articulation on modernity as “fleeting, transitory, and contingent" in 1863. He recognized that art has two facets: the fleeting, transitory, and contingent, in contrast to the eternal and immutable. Cen, evidently, has chosen the latter—the timeless and unchanging aspect, which persists regardless of the ever-evolving external world. As he sincerely stated in self-reflection, "In a flash, I realized—the intrinsic beauty of an artwork is the eternal pursuit of an artist." This pursuit transcends time and space, making this approach profoundly contemporary, as the critique and reflection upon modernity are fundamentally intrinsic to contemporary art.