Renato Cuttuso

Cen Long

8/30/2016

By Renato Cuttuso

When I first saw the oil painting "The Crucifixion of Christ" by Renato Cuttuso (1911-1987), born in Bagheria, Sicily, Italy, I felt that he was an artist I would particularly focus on in this lifetime. It was during the Cultural Revolution, in the late 1970s, when our whole family lived in a room of about twelve square meters. By then, I was already painting in the military, while my younger brother had gone to the countryside for labor.

In the large old church in the campus of the original Central South Nationalities University, the central hall was filled with bookshelves, haphazardly stacked with all the books from the former library of the university. Because the entire campus of the university had been occupied by the Hubei Provincial Military District, the school was simply dissolved. All the staff were transferred out, leaving behind a large number of books. At that time, the leaders of the Cultural Revolution considered books to be reactionary and useless, but it was a pity to throw them away. After all, they were school property, so they were packed into sacks and transported to this old church, which had once been piled with coal by some army.

Due to my father's situation, my mother was deemed problematic and not allowed to teach. Moreover, the history department of Wuhan Higher Education Institute was completely banned, so there was nowhere to go. We were temporarily placed in the original school's remaining office, where I was deprived of my qualification as a history professor and appointed as a librarian along with several other teachers who received the same treatment, to guard and organize these surviving books that had nowhere else to go.

After 1949, the church was converted into an auditorium for school gatherings, and it was empty inside. There were eight rooms on two floors at the four corners of the church, which were the former residences and storage rooms of the clergy. These temporary managers of the library and their families were accommodated in these small rooms. Cooking was done in the corridor, and to use the restroom, one had to go out and climb a small hill to the public toilet. The temporarily appointed library director lived elsewhere. Every day, under his supervision and command, a group of people carefully counted the books and compiled files, and then placed them on the old bookshelves brought in, awaiting disposal. The management was very strict, and no idlers were allowed in, because they were afraid that the reactionary knowledge would spread and pose a threat to the proletarian regime and spread reactionary toxins. At that time, besides revolutionary books, all kinds of books in bookstores had already been destroyed. I had been longing for this batch of books for a long time, but alas, there were people on duty, guarding, and working every day, so I had to wait eagerly for an opportunity.

One Sunday, in the cold winter with a cold wind blowing from the north, I returned home from the army. It was my mother's turn to be on duty, and just then we ran out of food at home, so she locked the door of the pantry and went out to buy groceries. I had long discovered that there was a nailed-shut door in our house that led to the large hall pantry, but the project was too big for me to handle. However, there were two small windows on the door that seemed to be nailed with only a few nails, so I took a pair of pliers, took off my padded pants, and pried open the windows. At that time, I was very small and thin, just enough to squeeze in and climb over. When I jumped from the window to the pantry, my clothes were all torn by the nails, but I didn't care. At that moment, haha, I felt like a mouse falling into a rice jar, excitedly with my heart pounding. My eyes quickly scanned between the crowded bookshelves, and suddenly I found a large pile of Soviet magazines "Spark" and "Artist" bound by year. Before the Cultural Revolution, "Spark" often published the best and latest paintings from the Soviet Union on the centerfold, and "Artist" magazine pasted paintings on the pages, all of which were copperplate color printed, and in those days, all foreign books and periodicals were absolutely not allowed to be lent out, so they were all brand new.

I grabbed many books and squatted down, frantically flipping through them. Whenever I saw colored pages, I tore them off and folded them into small pieces, quickly stuffing them into my shirt. When it became too full, I hurriedly put the magazines back, climbed out of the window, and returned home, putting on my padded coat as if nothing had happened. That night, I returned to the military base where I worked, where there was a room with my canvas set up, which also served as my bedroom. Under the desk lamp, I took out the fruits of the day's labor, tenderly smoothing them out while savoring them. I felt so happy in that moment that I didn't even care about the runny nose from catching a cold.

Subsequently, every weekend when my mother went out for duty, I repeated the same act. Eventually, I even assembled them into several large sketchbooks. I was glad that I had taught myself some Russian during my time in the countryside, so I not only understood the names of the authors but also the titles and summaries. These printed materials, with deep folds and broken edges, contained Western classical works familiar to me from the collections of the Altamira Museum, such as Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), as well as those of Russian itinerant painters from the Tretyakov Gallery, new works by young painters from the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries, and works and introductions of famous painters from Western Europe, South America, and Eastern Europe who had once joined the Communist Party, including Picasso.

However, when I saw Cuttuso's "The Crucifixion of Christ," I knew that he would be one of the painters I would never forget in this lifetime.

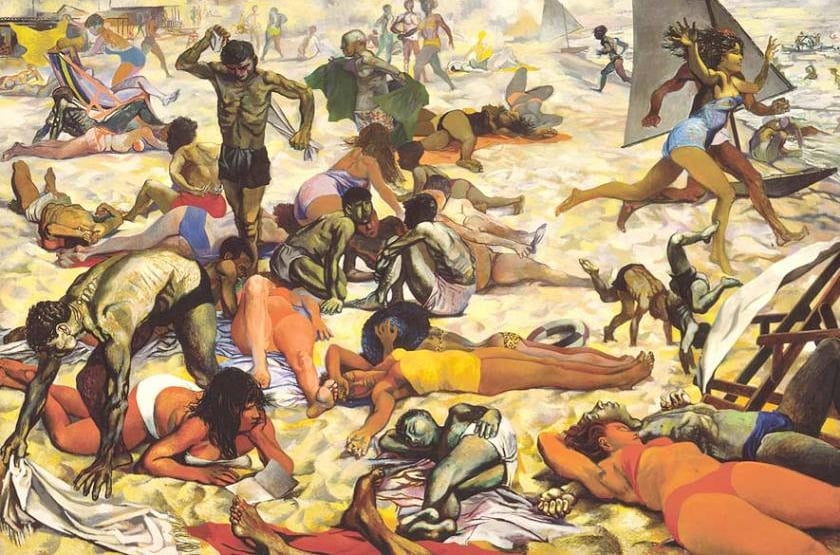

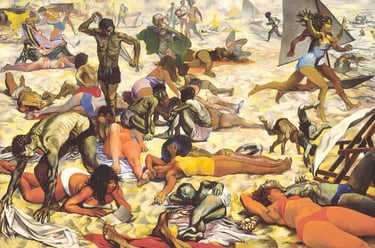

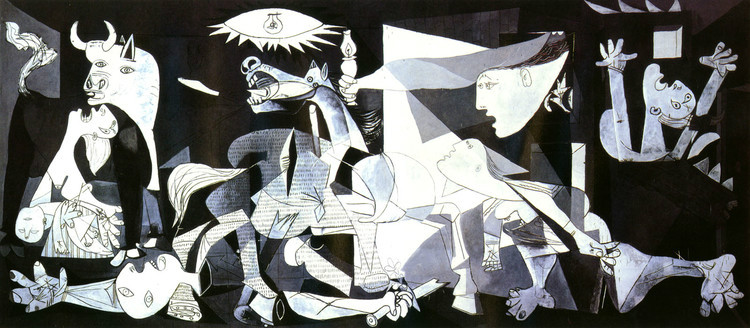

The style of this painting was completely different from the European classical paintings I had seen before, bearing resemblance to the cubist style of Picasso's "Guernica." The figures were almost completely nude, devoid of any era-specific features, treated in a flat manner with exaggerated and intense colors, expressing pain and despair. According to the introduction, this painting was created in the 1940s during the German invasion of Europe. Cuttuso used Christ's crucifixion to metaphorically represent the atrocities committed by the fascists. It had a unique theatrical effect, similar to the works of Caravaggio, with the tortured figure of Christ on the cross sculpted in high purity red, seemingly still pregnant with a passionate force amidst this terrifying image. The naked woman lying on Christ hanging on the cross and the two women crying with covered heads symbolized the grieving relatives of those martyrs killed by the fascists. A naked man representing fascist power, holding a weapon and riding a blue horse, walked among the crucified victims, while another held an iron spear with a torch for lighting and looked at the teeth of the tortured victims pulled out during torture. He stood next to a white horse with red cloth draped over it and eyes bloodshot from madness, waiting for nightfall. Nearby was a table with hammers, knives, scissors, nails, and strips of cloth used for execution, as well as two bottles of kerosene. The background depicted the aqueducts of Rome and typical Italian rural villages. Was this a scene of massacre and bloodshed?

At this time, during the late stage of the Cultural Revolution, the various scenes and feelings of cruelty and inhumanity I had just experienced seemed to faintly appear in Cuttuso's painting. Looking at this painting, I felt a piercing pain in my heart! I remembered my father, who had been tortured to death, and the countless innocent people I had seen at school and on the streets—former professors, capitalists, former small business owners, and so on—almost all of whom were elderly and weak, beaten with blood streaming down their faces, forced to hold up large black plaques weighing heavily around their necks with bleeding hands, bearing white characters falsely accused of being "reactionary ghosts and monsters," "reactionary academic authorities," and other crimes, with red paint crossing out their names. I remembered the fearful and helpless eyes of those people... I finally understood Cuttuso's heart. Whether victims or perpetrators, the figures in his paintings were all similarly naked, devoid of any distinguishing features. He wanted to confess: the external structure of human beings is similar, and what differs is their thoughts and ways of living. When evil thoughts triumph over conscience, it marks the beginning of human tragedy. When a few radical and selfish authoritarian rulers, for the sake of plundering and maintaining their own interests, resort to various means to incite and deceive the people, so as to achieve the goal of making the entire population unconscious or ignorant and blindly worshiping the upper class, they firmly control the behavior of the masses through compulsory means. At this time, society descended into a state of disorder, leading many people to lose their sanity and descend into madness and perversion. The struggles between people were actually clashes of different ideologies. Cuttuso was anti-Nazi, and he expressed his thoughts and positions through his paintings, condemning and criticizing the violations of humanity. I admired him because he dared to face reality. I knew that in the future, my own creations would inject understanding and comprehension of human nature into my work, just like him. I chose to inspire myself and others with kindness, believing that with more kindness in the world, there would be less evil.

Cuttuso used striking colors like blue, yellow, orange, and red, reminiscent of precious gems. Against the backdrop of dark colors and black lines, he created an atmosphere of unease and suffocation, leaving these colors imprinted on the irises of those who had seen his paintings for a long time. That was his extraordinary talent! Years later, the term "meaningful form" in art perfectly summarized his creative approach.

Returning to the later part of this story, one day, when I climbed back home panting from the window, I was surprised to see my mother's angry face. She had forgotten to bring money when she went out to buy groceries and returned home early to find my padded coat, pants, and sweater all lying on the floor by that window, with the window open. Immediately, she understood everything, her eyes filled with tears, without saying a word. I quickly nailed the window shut and hastily apologized to her, swearing that such a thing would never happen again, and then rushed back to the military base without saying anything else. But my heart was very uneasy because I knew what worried her the most was not that she might lose her job or be punished, but that her child had become a thief. It took me several weeks to nervously return home. My mother continued to buy groceries, cook, and do duty, without mentioning the incident at all. When I was about to leave, she suddenly stopped me and took out a large paper package from the drawer, handing it to me, saying, "Don't open it yet, go back and paint well." That night, when I opened the package, I found it filled with neatly cut-out pictures of famous paintings from sketchbooks and magazines. My eyes grew moist. After some time, one day when I returned home, my mother told me that the library manager had notified them that all foreign periodicals and magazines had been destroyed because they were deemed useless and taking up space, becoming a burden. She said they had burned them in the courtyard for two whole days, burning them thoroughly. At that time, the control was very strict to ensure that not a single word or paper was left behind, so as not to let any trace of reactionary ideology poison the people...