Cen Long and His Silver Age

Author | Huang Zhuan

10/1/2014

Cen Long is like an artist of the Silver Age, a man caught in the gap between an era of brilliance and one of absurdity. He yearns for the splendor of the Golden Age, yet laments its decline. Though he understands that such radiance will never return, he refuses to drift with the tide. Instead, he aspires to single-handedly create his own Silver Age—a transitional period poised between the sacred and the fallen. This vision shapes his art, keeping both his technique and his emotional expression imbued with a stillness and purity that stand in stark contrast to the flamboyance of our time.

Cen Long’s paintings blend the rigor of Classical Realism with the restraint of Expressionism. Through classical poetry, young girls, mountain villagers, farmers, ethnic minorities, and even anthropomorphized animals, he constructs an imagined utopia, a sanctuary for the homesickness of modern people who have lost their sense of belonging. His works retain a simplicity and wistful sentimentality, along with a nostalgia that drifts ever further from the sensibilities of the present age. He makes no attempt to conceal his longing for a world of benevolence and humanity—his art is an act of remembrance and homage to these fading virtues.His admiration for great art has led him to impose upon himself an almost uncompromising standard for artistic technique and quality, which he regards as both his responsibility and his ultimate purpose. He clings to the creed of "art for art’s sake" with a steadfastness that feels almost anachronistic in our time. As a result, when we turn to his works—having grown accustomed to the vanity and exaggeration of postmodern imagery—we may feel as if we are encountering something from another era, imbued with a sense of distance and antiquity.

Cen Long was born into an intellectual family in the mid-20th century. His father, Cen Jiawu, was a pioneer in Chinese ethnology and anthropology, while his mother was a historian. In the academic history of China, his father's book, History of Totem Art, published in 1937, is regarded as a groundbreaking work in the field of Art Anthropology. However, like many intellectuals of his time, Cen's father, who was serving as the Dean of the South Central University for Nationalities, became a primary target during the Cultural Revolution. Persecuted to death at the age of 54, he became a tragic figure in the turbulent history of modern Chinese academia.From his father and family, Cen inherited not only a natural artistic inclination, a refined upbringing, and qualities of elegance, honesty, and humility but also a certain reserved arrogance and a tendency toward solitude. A brief period of his childhood spent in France left an indelible mark on him, shaping his understanding and appreciation of Western art. Even today, he maintains a profound interest in Chinese classical art, European Romanticism, and Russian literature and poetry from the Golden Age to the Silver Age. His love for classical music—ranging from the Baroque period to the early Romantic era—remains an integral part of his daily life.His artistic influences extend beyond visual arts and literature to cinema. He has an extensive familiarity with films spanning from early Impressionism and Expressionism to various New Wave movements, and he has deeply engaged with the works of Jean Renoir, Alfred Hitchcock, Luis Buñuel, Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson, Federico Fellini, Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais, Bernardo Bertolucci, Michelangelo Antonioni, Theo Angelopoulos, Roman Polanski, Krzysztof Kieślowski, Andrei Tarkovsky, Yasujirō Ozu, Akira Kurosawa, Werner Herzog, and Michael Haneke.Yet, unlike many of today’s young artists, his passion for these disciplines is not a means of conversation, entertainment, or self-display. To him, these artistic interests serve as a vital sustenance for the soul, a medium through which he connects with his inner utopia, maintaining an essential equilibrium in life. Without them, he would find it nearly impossible to confront the restless, clamorous outside world—let alone engage in artistic creation.

Over the past forty years of Cen Long's artistic journey, Chinese painting has undergone a transformation—from ideological realism to various forms of radical modernism and postmodern imagery. Yet, despite the complexities of these shifting times, Cen Long’s original devotion to painting has remained steadfast. For him, painting is not merely a craft but a means to contemplate life and express emotions. Perhaps, in his world, only painting can provide the courage, solace, and hope he seeks. Cen’s early works were deeply influenced by European classical realism, romanticism, and impressionism. His mastery of form and his almost feverish brushwork are evident in both his portraits and figurative compositions, such as Girl in Red, Young Boy with a Red Scarf, Actor in the Children's Theatre, and Morning in Akesu. During the fervent modernist movement of the 1980s, Cen briefly experimented with modern expressionism and sought kindred artistic spirits in the lineage of modern painting. Among them, he found Egon Schiele, an Austrian artist whose work resonated with him both spiritually and stylistically. Schiele’s expressionist style evolved from the decorative techniques of his mentor, Gustav Klimt, incorporating elements of ukiyo-e’s linear traditions and flattened deformations. However, what distinguished Schiele was his highly neurotic approach to depicting human movement and expression. The tension between his subjective color palette and his disciplined formal structures set him apart from the raw intensity of early German Expressionism. This dynamic interplay between strong individuality and controlled rationality became a defining quality that Cen Long, too, sought to achieve in his own work. Paintings such as Kashi Night, Red Moon, Self-Portrait, Love, and especially Twilight Snow reflect this influence. Created in 1987, when Cen was thirty, Twilight Snow was both a milestone of artistic maturity and a self-reflective statement. The painting presents a low-angle perspective of a secluded mountain landscape, where geometrically deformed peaks and somber, expressive brushstrokes combine to evoke a deeply oppressive atmosphere. At the heart of the scene, a donkey struggling along a rugged mountain path stands as a metaphor for the artist himself—a solitary figure, unyielding and unwavering in his pursuit, destined to walk his path alone, yet without regret.

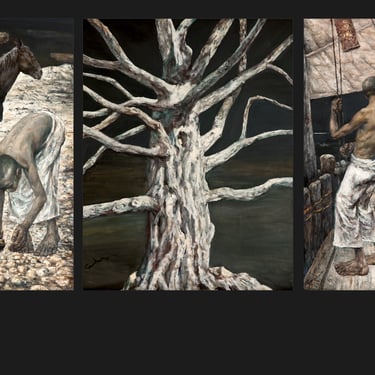

Cen Long has always lived in the city, yet the settings of his works are predominantly mountainous landscapes and rural villages. His choice of subject matter differs from the “return to nature” ethos of early realism, as well as from the visual experimentation of impressionism and post-impressionism. Rather than a stylistic or ideological stance, his motivation appears to be deeply psychological: a subconscious defiance against urbanized civilization and a manifestation of his imagined utopia.In works such as Afar, Pony, Story, Childhood, Stable, and Little Silvie and I, one can discern another significant influence on his imagery: the folk painting traditions of 16th-century Pieter Bruegel the Elder. If Schiele provided him with a means to articulate the solitude of the individual in the modern world, Bruegel’s allegorical folk narratives offered him a sense of psychological refuge for those who have lost their homes in the tide of modernity.In what critics have termed his “Purgatory Period” and “Bard Period”, Cen turned his gaze toward the farmers of northern Shaanxi and the nomadic people of Xinjiang, seamlessly integrating subjective imagination with naturalistic depiction. The result is a series of self-contained, symbolically charged idealized worlds, where his pursuit of a personal utopia reaches a quasi-religious intensity.

Cen’s paintings function as narrative myths, chronicling the journey of lost modern souls in search of home, while simultaneously serving as psychological records of this odyssey. In these visual recollections, one finds both tender, melancholic storytelling and profound laments for times long past. In Windy Wilderness, Weaned Calf, and Silver Land in Twilight, he distills the theme of loss into rustic narratives of companionship between humans and their animal counterparts, embedding the existential conflict of displacement into scenes suffused with poetry.Works such as Nomadic Life, Overlooking Muztagh Ata, Rawap, White Horse, The Hawk, Purgatory (Triptych), Sunset Over the Earth, and Mountain Winds are active narratives exploring the relationships between humans, animals, and nature. Yet, like music and stream-of-consciousness literature, Cen deliberately minimizes explicit narration, creating a vast interpretive space for the viewer to engage with his art on a personal level.

The art historian E. H. Gombrich once referred to those unknown, unyielding artists—who resist the pressures of fashion, vanity, and commercialism—as “underground” artists (Art and Science). In an art world that drifts ever further from its past, these artists uphold their artistic integrity, confronting the flux of modernity with an unwavering commitment to their ideals. Cen Long is precisely such an artist—a man of vision, living within the world of his own imagination. He knows that all his efforts serve a single purpose: the creation of his own Silver Age, a world that belongs to him alone.

(Acknowledgment: This article references The Singer Above the Clouds by Ms. Lin Xuanhan.)

— Huang Zhuan, Professor of Art History, Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts