A Tale from the Past

Cen Long

9/30/2016

Due to my parents' connections, I was exposed to Chinese art history at an early age and developed a deep love for ancient Chinese painting. During several vacations in high school, my father tasked me with labor at the Palace Museum, participating in activities like airing out paintings and cleaning artifacts, as part of my social practice and training. Perhaps this was to prepare me for my future, as he knew of my early passion for painting. However, at the time, pursuing a career related to art, especially one involving higher levels of society, was considered a "high-risk" profession, prone to "political errors." Because my father had suffered greatly in the past, he wanted me to learn practical skills related to art but not directly involved in artistic creation.

My father pleaded with the head of the Palace Museum's research institute to accept me and specifically invited several senior researchers to supervise me rigorously. These included his old colleague and friend, the archaeologist Gu Tie Fu, as well as Mr. Han Huaizhun, an expert in exporting ancient Chinese porcelain and a fellow Hainanese compatriot. Through their enthusiastic guidance and teaching, I had the opportunity to witness and engage with many precious artifacts up close, truly experiencing the profound depths of ancient Chinese culture. The valuable essence contained within these artifacts far surpassed what could be explained by the generic discussions found in published works on Chinese art history.

Apart from participating in daily cleaning and display tasks during the day, the elder gentlemen required me to read extensively from the professional books they designated at night. To use Mr. Han's phrase, it was all about "cramming for the exams!" These books included ancient texts on the history of painting and ceramics, as well as historical documents on customs from various periods, such as "New Sayings of the Tang Dynasty," "Ink Garden," "Record of Dreams of the Capital of the East," "Record of Dreams of the Liang Dynasty," and "Old Stories of the Martial World." Whatever period of artifacts I worked with during the day, I had to read books from the corresponding era at night. Their homes were filled with books, and sometimes they would borrow books from the Palace Museum's research institute for me to read, overseeing and checking my reading summaries. They were stricter with me than with their own children, supposedly to be accountable to my father.

At that time, the level of personnel in the Palace Museum's research team was very high. Some of the prominent figures known today were just ordinary staff members at that time. They possessed a high level of professional knowledge and, in addition to their regular work, were diligently conducting their own research, sometimes to the point of obsession. Those individuals wearing white gloves to unroll paintings or wipe porcelain might have become famous figures later on. Listening to their conversations on a regular basis was truly enlightening. They often told me that artifacts had a life of their own; they could tell their own stories. Did I want to listen? Well, then I must first love them and establish a connection with them. Under the influence of these senior figures, I quickly learned to immerse myself in the era of those calligraphy, paintings, and artifacts, forgetting about my original reality and gradually narrowing the distance between myself and them, which brought me immense joy and delight.

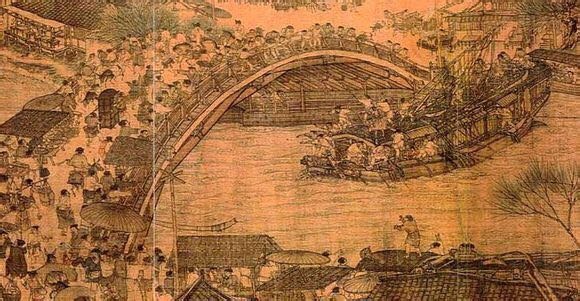

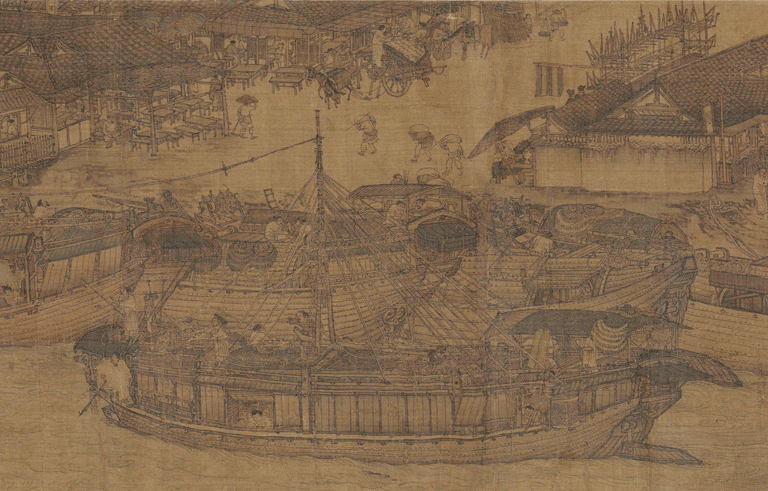

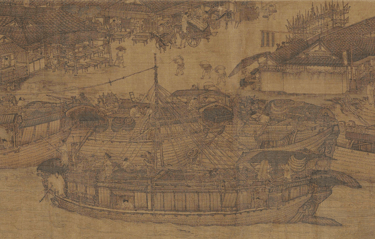

When I first saw the original "Along the River During the Qingming Festival," I was simply astonished. My family had a printed version published by the Palace Museum, and even then, it was relatively clear, but I never imagined the original painting would be so small. It was only about twenty-something centimeters wide but over five meters long. The display cabinets were not long enough due to poor equipment. During the exhibition, or rather, the open display, they would unroll only a portion for the audience to admire for a few days before rolling it back up and displaying another part. Every time they unrolled a section, I couldn't help but linger for a long time, almost pressing my nose against the glass.

The taverns, inns, and the illuminated advertisements of Zhao's household suddenly felt familiar. I seemed to hear the braying of donkeys and the neighing of horses, and smell the fragrance of fried cakes, Hu pancakes, and mutton soup. I became one of the figures in the painting, mingling with the bustling crowd, watching the hustle and bustle, while sedan chairs and mule carts squeaked past. I stood on the banks of the Bian River, watching the huge wooden ships being propelled through the winding Rainbow Bridge by urgent boatmen wielding poles... I was no longer a stranger to the Song Dynasty; I imagined myself as a participant in that scene. I began to think about how I, if I were the painter Zhang Zeduan (1085-1145), would handle such a complex and vast scene. I had seen many large-scale paintings abroad, but never had I seen such a variety of characters, actions, and unique poses, each meticulously detailed and vividly portrayed without repetition. Groups of figures were dispersed or gathered in a balanced manner, in motion or at rest, echoing each other, vividly alive in every detail. Although Chinese painting emphasizes distant perspective, the visual perspective of pedestrians, carts, and houses in the painting was handled very well, appearing both rational and natural. Looking closely at those lines, most were precise and controlled, transitioning smoothly with rigorous turns and meticulous attention to detail, neither rushed nor careless. The dynamic shapes and proportions of the figures were meticulously crafted and well-balanced, captivating and keeping viewers glued to the display cabinet. Since then, I have seen many other versions of "Along the River During the Qingming Festival," but none have moved me as deeply as that one.

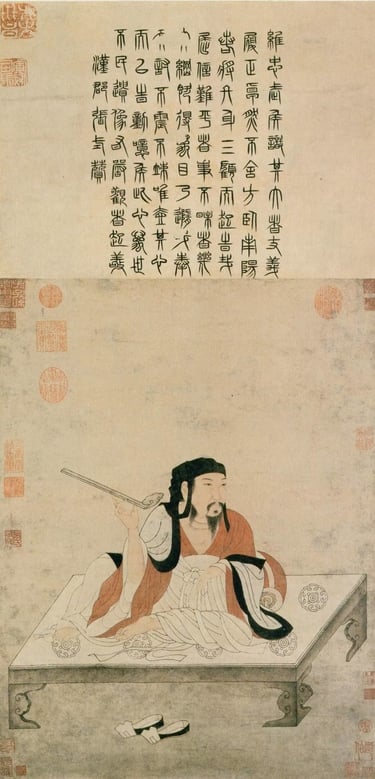

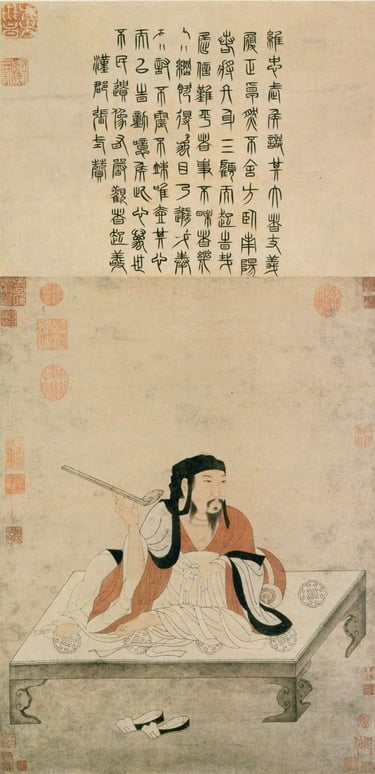

Another painting that left a strong impression on me was a portrait from the Yuan Dynasty: "Portrait of Zhuge Liang," attributed to an anonymous artist, painted on a hanging scroll and rarely displayed. Once, during an exhibition of ancient portraits at the Palace Museum, it was hung up for display. It was a meticulous painting depicting Zhuge Liang wearing a black headdress, a dark red robe, and a gray-white gauze draped over his shoulders, sitting with his legs folded on a couch. His right hand held a ruyi scepter, symbolizing his status, and his eyes gazed forward, as if lost in thought. The entire painting was dominated by shades of light gray, with the skin of the figure painted in flat colors but slightly enhanced with subtle shading to create a sense of depth. The composition was simple and minimalist, with a sparse background of a gray-white bed surface, with only a pair of shoes placed in the foreground, echoing the figure in the composition. The fluid, flowing lines of the silk thread added a sense of elegance and ease to the figure. Although there was no detailed depiction of the background, the empty gray backdrop did not appear monotonous; instead, it formed a mysterious aura enveloping the subject.

The style of this painting was very elegant and distinct from the ink or heavy-color figure paintings filling the exhibition hall. I compared it with European paintings I had seen; a simple background actually allows viewers to focus more on the portrayal of the figures without being distracted by intricate background details. Of course, detailed backgrounds can recreate the real scenes of painting events and serve to enhance the theme, each having its own merits. Chinese painting mainly emphasizes the spirit, while the West pays more attention to atmosphere. Of course, this is only a superficial distinction; in fact, the

goal pursued by human art is entirely the same: to touch the hearts of the audience and convey the artist's thoughts.

I gradually learned to engrave the good paintings I saw into my mind, not just seeing with my eyes but thinking with my heart, comparing different authors' intentions and techniques. I knew that while understanding the differences between Chinese and Western painting styles, it was even more important to explore the common essence of artistic creation.

In the end, I did not follow my father's wish to become a cultural relic preservation worker, let alone a researcher... For this reason, Mr. Tan Weisi, the director of the Hubei Provincial Museum, once had a serious conversation with me, but that's another story.